Exploring Liminality in Magic and Storytelling

September 03, 2025

“The mind is a fragile thing; it can erase and distort what once seemed real.” – Mark Z. Danielewski

When I say the words “liminal space” together, it likely evokes images of empty beige hallways, stretching corridors with no other life but your own to disturb the peace, you likely see “the backrooms.” I expect that in today’s era of creepypastas and SPC fandoms on the rise.

However, while the word liminal—from the Latin limen, which means “threshold” —can be used to describe a space, it is also commonly used in literature and storytelling to describe the unknown within time, or the “in-between.”

Because of this, we often see liminal space-time as a vehicle for transformation. The dark of night must always break for the light of day, but on the edge–right there before dawn—we find the liminal. What if the sun doesn’t rise? Why does it feel slower this morning? This moment is itself a threshold. A magical place between what we know, our current state, and what comes next, the unknown. We see this technique used all of the time for jump scares in movies, eerie paths taken in books, and even in the games we love like…I don’t know…Magic the Gathering, for example.

Just as authors use liminal spaces and moments to unsettle and transform their stories, Magic: The Gathering storytellers harness liminality in both narrative design and worldbuilding–generating suspense and emotional resonance across sets. Two notable examples of this would be the Blind Eternities themself and even 2024’s banger set Duskmourn. Today I want to explore this literary device, discuss what makes it so fascinating to me and then analyze how Wizards has used this to expand the multiverse as we know it.

Does this Valley Seem Uncanny to You?

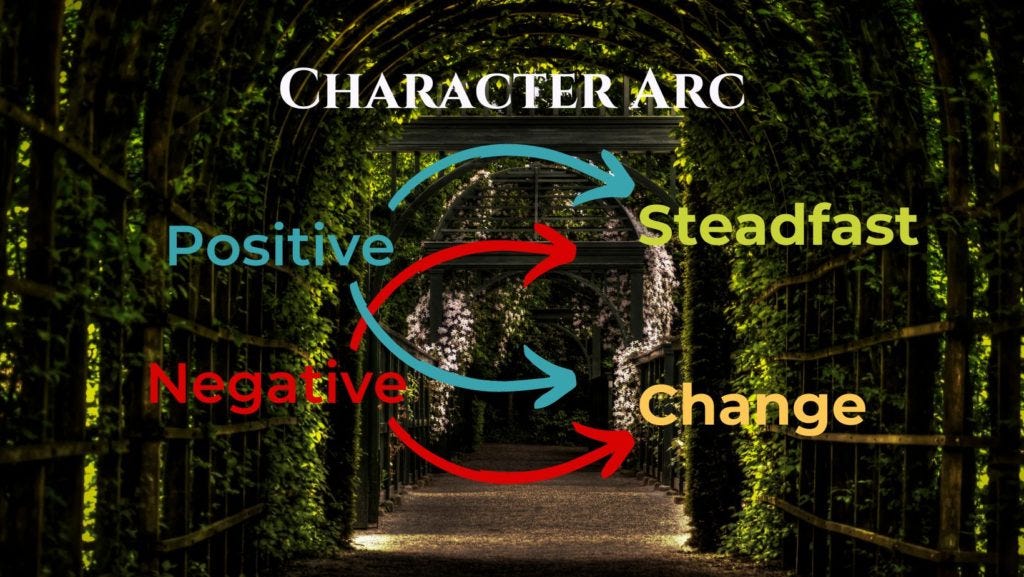

Now, when we talk about liminality in stories, we’re often talking about the “messy middle.” It’s the part of the journey where the old self has already been stripped away, but the new self hasn’t quite emerged. Writers like to use this space because it forces their characters, and us, to sit in the uncomfortable in-between. Joe Bunting over at The Write Practice describes liminality as destructive, chaotic, and ultimately transformative. And honestly, that tracks. Think about Raskolnikov in Crime and Punishment, spiraling in guilt after the murder but long before any kind of redemption. Or Luke Skywalker, training in exile on Dagobah, not quite a farm boy anymore but nowhere near the Jedi we eventually see. These are the moments where identities wobble, where everything feels uncertain, and that uncertainty is what makes the transformation believable.

But liminality isn’t just about character arcs—it’s also about the atmosphere that surrounds them. Melissa Harkin calls liminal spaces “pause points.” They’re those stretches of story where time feels a little warped, the air feels heavier, and emotions are allowed to simmer before something big breaks. A good liminal moment is like holding your breath. Think about that taxi scene in Lost in Translation–neon blurring past the windows, the silence between two people heavy with things unsaid. Nothing “happens” in that scene in the traditional sense, but it lingers.

That’s liminality doing its work on you, the audience.

Of course, horror has arguably made the most of this trick. Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves practically drew the blueprint on liminality—endless hallways, impossible architecture, layered narratives that never give you solid ground to stand on, it all quietly screams at us to wait for the unknown next.

![House of Leaves [Book Review] - Room Escape Artist House of Leaves [Book Review] - Room Escape Artist](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!tyrv!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F500b101d-c040-4692-a900-79f82318952e_4160x3120.jpeg)

Danielewski’s fingerprints are everywhere now: The Blair Witch Project’s raw, “found” footage; creepypastas like Ted the Caver or The Backrooms; even games like Control and Alan Wake that twist space and story into a surreal playground. Horror doesn’t just put a monster in the room; it makes the room itself uncanny. That’s the power of liminality.

Whether it’s a character caught between who they were and who they’ll become, a moment suspended in a dreamlike atmosphere, or even a literal hallway that stretches into the impossible, liminality is the secret spice that makes stories resonate. Try to imagine Kubrick’s The Shining without any of the Overlook’s hallways, without the countless closed doors. You can’t, because it’s where the tension gathers, where meaning deepens, and where we, as the audience, really start to feel the world bending under our feet.

And, if you want to get real scientific about it, psychologists have actually shown that distorted or irregular architecture can make us uneasy. Alexander Diel and Michael Lewis found that “structural deviations” in places like a hallway that bends too sharply or a room that’s just a little too long trigger a response similar to the uncanny valley. Put a human being in that space, and the eeriness amplifies.

Our brains want spaces to “make sense,” and when they don’t, the liminal takes over. Again, when we move from our current state and have to cross to the unknown, we feel very real fear. No matter how impactful or heavy that fear, it is there.

Do You Have Threshold?

So, if liminality is all about thresholds, then we know that Magic: The Gathering practically swims in it. I mean, the game’s entire multiverse is built on the idea of moving between worlds, between selves, between what is known and what lies beyond. Hell even pllaneswalkers themselves are liminal by definition, after all they’re characters who can exist in that space between planes, stepping through the Blind Eternities, that raw, chaotic void of possibility.

Wizards of the Coast has leaned into this imagery for years, describing the Eternities as both infinite and hostile: a realm of pure transition, where nothing is stable, but everything is possible. It’s not a destination–it’s the liminal space that connects all destinations.

And then there’s Duskmourn: House of Horror from 2024, which might be the most overt love letter to liminality in MTG’s history.

Duskmourn takes the haunted house, a classically liminal setting where doorways stretch into impossible hallways and rooms refuse to end and blows it up into a whole plane. Like Danielewski’s House of Leaves, it uses space itself as the villain. You’re never sure if you’re walking through a normal room or into something that rewrites the rules of physics. This isn’t just a place where horror happens, this is a place where space itself is the horror. That’s liminality at work, turning architecture into narrative tension.

But Magic’s storytellers don’t just use liminality for spooks. They use it to build suspense and to deepen emotional arcs.

Think about Ajani’s grief in the wake of Elspeth’s death, he’s caught in that destructive, chaotic middle ground where his old sense of self has been burned away, but the new one hasn’t quite formed. Or Liliana Vess after the fall of Bolas, hovering in the uncomfortable space between villain and reluctant ally. These aren’t just plot points; they’re the liminal “pause points” that let us feel the characters struggling to redefine themselves before their next transformation.

Even the game mechanics echo this design. “Exile” is literally a liminal state—cards removed from play but not gone forever. Suspended spells hang in that in-between space, waiting for the right moment to resolve. Transform cards—whether it’s Innistrad’s werewolves or Duskmourn’s dread manifest–live at the threshold between one identity and another. These mechanics aren’t just flavor; they embody the narrative power of that in-between.

And that’s why I think that liminality works so well in MTG’s worldbuilding. Just as distorted hallways in horror fiction make us uneasy, distorted rules and shifting identities in the game keep us hooked. Magic thrives in this ambiguity–in these thresholds where characters, players, and even entire planes are not one thing or another, but both, or neither, or something waiting to be revealed. It’s that in-between where suspense gathers, where the storytelling deepens, and where Magic feels less like a card game and more like a living, breathing myth.

The Space within the Game

At its heart, Magic: The Gathering explores liminality through possibilities. Every drawn card, every decision made in-game, every branching storyline is a step into the unknown. That’s why liminality feels so at home here: it mirrors the experience of playing the game itself. Liminal spaces and moments thrive on tension—the not-knowing, the waiting, the shift that’s about to happen but hasn’t yet. That’s the same tension you feel holding an instant-speed spell in your hand, watching your opponent weigh their options, or waiting to see if your top deck changes everything.

From a storytelling perspective, liminality works in Magic because it amplifies both suspense and transformation. The Blind Eternities don’t just connect planes—they create a constant sense of instability, a reminder that even the fabric of the multiverse is transitional. Characters, too, often find themselves caught in liminal arcs: not just heroes or villains, but something unsettled in between, reshaping before our eyes. That ambiguity makes them feel more human, more real, even in a world of dragons, demons, and gods. Think about Jace here. In the end of Dragonstorm’s story we are left wholly unaware of where he is or what he is planning to do with the Ugin’s Gem. We are living in liminal space, many of them to be fair, all of the time.

That is definitely purposeful as well. Liminality keeps us, the audience, invested because it never lets us get too comfortable. It keeps stories alive by holding us in that threshold moment where everything could change. In a game built on imagination, unpredictability, and the thrill of transformation, liminality isn’t just a theme—it’s the perfect storytelling tool.

“Sometimes, seeing is not believing.”

Liminality thrives in the spaces we don’t fully understand—the thresholds where rules blur, time stretches, and the next step feels both inevitable and uncertain. Literature has long used these in-between moments to unsettle us, to force transformation, or to let us glimpse the uncanny just past the edge of the ordinary. And Magic: The Gathering taps into that same well of unease and possibility. From the Blind Eternities to the twisting corridors of Duskmourn, from the emotional “pause points” in characters’ journeys to the very mechanics of exile and transformation, liminality is baked into the way Magic tells stories.

What makes this so compelling, at least for me, is that liminality never offers easy answers. It asks us to sit in uncertainty for a while. To let the hallway stretch longer than we expect, or the night linger before the sun rises. And in doing so, it makes the eventual resolution–whether that’s a jump scare in a film, a character’s rebirth in a novel, or a planeswalker’s next step across the multiverse—hit all the harder.

So the next time you play a game of Magic, or read through a set’s story, take a moment to notice those thresholds. The half-formed, the unsettled, the not-quite-here and not-quite-there. Because it’s in those moments, those liminal spaces, that both stories and games find their most haunting and transformative magic.

Leave a comment