Boggarts, Old English Folklore, and the Hunger at the Heart of Lorwyn

January 23, 2026

You never see a boggart at first.

You notice the absence instead.

The spoon that was on the table. The coin you swear you set down. The sound of something laughing just a little too far away to chase. In the old stories, a boggart never announces itself with claws or fire or with anger or even attacks, it does so by making you doubt your own memory.

This is important, because boggarts were never meant to be monsters in the heroic sense. They aren’t dragons to be slain or even demons to be banished. They are your neighbors, lend them some sugar.(Sorry) They live in the margins of your home, your field, your routine. They are the explanation that you reach for when something has gone wrong and no one is willing to take responsibility.

Which is why it’s so striking to me that when Wizards went looking for a place to put them, it didn’t modernize them. It didn’t clean them up. It didn’t turn them into jokes or tragic antiheroes. Instead, on the sunlit, storybook plane of Lorwyn, Magic let boggarts stay exactly what they’d always been: hungry, cruel, loud, and impossible to fully control.

Lorwyn is a world obsessed with memory, stories passed down, roles inherited, traditions so old they feel inevitable. And in a place like that, boggarts aren’t outsiders. They’re part of the ecosystem. They steal, they burn, they fight, and they survive. Not because they’re clever like the Elves. Not because they’re righteous like the Noggles. But because folklore has always made room for things that don’t behave.

Now, to understand why Lorwyn’s boggarts feel so right, we have to go backward. Past card frames and creature types. Past goblins and goblin kings. Back to muddy fields, half-whispered warnings, and a word that once meant: something is wrong here, and it might be watching you.

This is where boggarts come from.

Where the Word Comes From

The word boggart doesn’t arrive with a single, clean definition. It creeps in the same way the creature does: through regional speech, half-agreed meanings, and a long lineage of fear-words that blur together over centuries.

Linguistically, boggart is most often traced to northern English dialects, particularly Lancashire and Yorkshire, with roots in earlier Middle English and Old English terms related to fear and haunting. The Oxford English Dictionary connects boggart to the broader family of words that include bogey, bogle, and bugbear; all descendants of the Old English bugge, a term used for something frightening or uncanny rather than something physically monstrous.

Katharine Briggs, one of the most influential folklorists of British fairy tradition, describes boggarts not as a species with fixed traits, but as a category of presence:

“The boggart is essentially a spirit of place, malignant or mischievous, haunting a particular house, farm, or stretch of land.”

— Katharine Briggs, An Encyclopedia of Fairies (1976)

This idea, that boggarts belong to a place, is crucial. Early boggarts were not wandering beasts. They didn’t emerge from caves or distant forests. They were domestic in the most unsettling way. They lived in your barns, under stairs, along hedgerows, and at the edges of fields. You couldn’t even “hunt” a boggart. You simply endured one.

In many early accounts, boggarts are described less by what they look like and more by what they do. Milk that curdles prematurely. Tools that just go missing. Footsteps echo in empty rooms. Children would refuse to sleep. Livestock would panic for no visible reason. The boggart is the narrative glue, the scapegoat, holding these disruptions together.

Importantly, these early boggarts are not inherently evil, nor were they necessarily viewed as such. They are simply reactive. They lash out when they’re disrespected, ignored, or displaced. In some traditions, a boggart only becomes violent when its home is threatened, when a farm is sold, a boundary crossed, or a family attempts to flee without acknowledging it.

All of this gives us a creature defined by resentment and memory rather than ambition. A being that remembers where it belongs, even when humans try to forget.

Stories They Lurk In: Boggarts in British Folklore

Unlike kings, heroes, or dragons, boggarts rarely star in grand myths. They exist in anecdotes, warnings, and local histories; stories told to explain why a place feels wrong, or why a family never quite prospers.

“Where’d that other sock go?”

“Boggart probably got it.”

One of the most frequently cited examples comes from Lancashire folklore, where boggarts are said to attach themselves to specific households. In one recurring tale, a family attempts to escape a tormenting boggart by moving away—only to hear it laugh as it rides along in a cart piled high with their belongings.

The folklorist William Henderson recounts a version of this story in Notes on the Folk-Lore of the Northern Counties of England (1879), where the boggart famously announces:

“Ay, ay! we’re flitting, ye see.”

— William Henderson (1866)

The line is playful, almost charming, and deeply unsettling. The boggart isn’t bound by walls or ownership. It is bound by people. By proximity. By familiarity.

Other regional stories paint boggarts as shape-shifters or mimics, capable of imitating voices or appearing as animals to lure travelers off safe paths. In Yorkshire tales, boggarts are sometimes indistinguishable from bogles (figures that frighten for the sake of fear itself, with no clear moral lesson attached).

Briggs again emphasizes this instability:

“Boggarts are among the least reliable of spirits; they may be helpful one day and destructive the next, and no bargain with them can be fully trusted.”

— An Encyclopedia of Fairies (1976)

What unites these stories is the scale. Boggarts don’t threaten kingdoms, for example. They threaten your small routines. They just steal a little food, trip some horses, sour the milk, or even whisper at night. They are the folklore of laborers, farmers, and children; the people most vulnerable to small disasters compounding into ruin.

This places boggarts in stark contrast with fairies of courtly tradition. They are not whimsical. They aren’t elegant. They don’t offer wonder or bargains, and they definitely don’t care about your name. They just offer inconvenience, fear, and loss. And in doing so, they become expressions of anxiety tied to survival itself.

So, by the time we reach Lorwyn, Magic isn’t borrowing a monster, it’s borrowing a social role. One shaped by hunger, resentment, and the quiet violence of scarcity; a role that fits disturbingly well into a world built on tradition, memory, and what happens when you refuse to move aside.

Lorwyn’s Boggarts: Not Reinvented, Remembered

Lorwyn’s boggarts don’t feel designed to me.

They feel unearthed somehow.

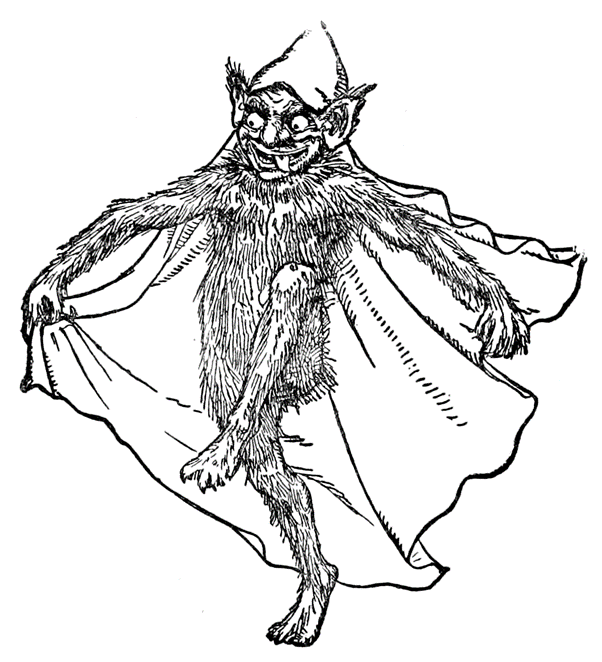

Their bodies are wrong in ways that feel intentional rather than exaggerated. Limbs that are too thin versus heads that are too large. Mouths that dominate everything else, stretched wide in hunger or laughter or both at once. Even at rest, they look like they’re mid-motion, caught between grabbing and fleeing.

This isn’t just grotesque fantasy art, it’s folklore logic made visible. Boggarts have always been defined by appetite before identity. They’ve never been warriors, or builders, and certainly not rulers. They are mouths. Lorwyn understands this, and it never lets you forget it.

Culturally, boggarts exist on Lorwyn as scavengers and raiders, living off what others grow, make, or protect. They don’t farm. They don’t preserve. They accumulate, burn, and move on. Their camps, or Warrens, feel temporary even when they’ve stood in the same place for years: heaps of stolen objects, half-functional shelters, and the lingering sense that nothing here is meant to last.

They also aren’t unified.

There is no boggart nation, no shared destiny, no myth of a better future. Even their leaders feel provisional. Mad Auntie and Wort, Boggart Auntie aren’t queens in any traditional sense. I believe it’s also because the longer a Boggart survives the more magic it possesses, though that is an MTG specific concept and not necessarily tied to their origins.

Nevertheless, they are tolerated, listened to, and followed because they’ve survived long enough to matter, not because anyone necessarily believes in their right to rule.

That, too, is folklore accurate. Authority among boggarts is temporary. Conditional. Always one bad decision away from collapse.

When you place boggarts beside Lorwyn’s other tribes, the contrast sharpens. Kithkin are order and memory. Elves are beauty and hierarchy. Merfolk are knowledge and flow. Giants have purpose. Even Flamekin burn toward something.

Boggarts don’t.

They live in the negative space, or the spillover. The places where harmony fails.

Lorwyn doesn’t push them to the edges of the world. It keeps them uncomfortably close to us at the borders of villages, the edges of paths, the places where the pastoral fantasy begins to fray. They are the reminder that every idyllic system produces waste, and that someone has to live there.

Mischief in Mechanics

If Lorwyn’s art teaches you what boggarts are, then its mechanics teach you how they feel.

Playing with boggarts is never stable. Not for your opponent, and certainly not for you. Their cards trade longevity for immediacy, permanence for impulse. Creatures die quickly with mechanics like Blight. Resources disappear suddenly through Discarding. Advantage comes with a price, and that price is often paid by the player who thought they were in control.

This is the core of their mechanical identity: instability.

Sacrifice is everywhere.

Creatures are thrown away for damage, for cards, for fleeting momentum. Discard appears not as careful hand management, but as sudden loss—plans ripped out of your grasp before they can settle.

Even their aggressive creatures feel reckless, daring you to overcommit because that’s exactly what boggarts would do.

They don’t plan for the late game, they consume the present.

What’s notable here is how rarely boggart mechanics reward cleverness in the traditional sense. You aren’t building elegant engines or assembling inevitability. You are accelerating entropy. Making bad situations worse. Pushing the game toward collapse and hoping you’re better at surviving the fallout. Cards like Mornsong Aria, despite being Elven, feels very Boggart to me, for example.

Even their tribal synergies feel fragile. Kindred spells exist, but they don’t create security, rather they create pressure. Lose one piece though and the whole structure wobbles. It’s a tribe that can implode just as easily as it can overwhelm.

And then there’s the humor.

Not playful. Not whimsical. But cruel, sharp-edged, and uncomfortable. Boggarts hurt themselves. They hurt each other. They hurt you. The game becomes a space where chaos isn’t just present, it’s encouraged.

In this way, Lorwyn does something rare. It doesn’t just adapt folklore into mechanics. It adapts folk behavior. The anxiety of scarcity. The violence of hunger. The way mischief escalates when no one has enough to begin with.

Again, you don’t master boggarts, or even barter…you just endure them.

Still Stealing Silver

You still don’t see a boggart first.

You notice what’s missing.

That absence, of food, of safety, of certainty, is where boggarts have always lived. In the gaps between what a system promises and what it actually provides. In the quiet resentment that builds when survival feels like a competition instead of a guarantee.

Lorwyn understands this. It doesn’t explain its boggarts away. It doesn’t redeem them. It doesn’t give them a grand myth to soften their edges. Instead, it lets them remain what folklore always intended them to be: uncomfortable, disruptive, and impossible to fully contain.

Afterall, they’ve been known to laugh when things fall apart.

I can’t stress this enough though, and it is this way for most classic Fae entities, it is not because they are evil, but because something must always lives at the margins of every pastoral dream.

In Lorwyn, boggarts aren’t a failure of the world’s design. They are proof that the world is working exactly as it always has. Harmony maintained by exclusion. Beauty protected by pushing hunger elsewhere. Order preserved by pretending the cost isn’t listening from the hedgerow.

And somewhere, just out of sight, something is still laughing.

Because something is still being taken.

And you’re only just now noticing.

Sources:

Henderson, W. (1866). Notes on the Folk-Lore of the northern counties of England and the borders. Notes and Queries, s3-X(259), 486. https://doi.org/10.1093/nq/s3-x.259.486d

Briggs, K. M. (1976). An encyclopedia of fairies : hobgoblins, brownies, bogies, and other supernatural creatures. In Pantheon Books. http://ci.nii.ac.jp/ncid/BA03093453

Leave a comment