Why Magic’s Monuments Refuse to Crumble

January 02, 2026

Editor’s Note: For the purposes of this piece, I am focused solely on cards that have the title of Monument in their name. I do recognize that cards like The Monumental Facade, Shrines, and the like are all technically monuments by definition.

Recently I reread Percy Bysshe Shelley’s sonnet Ozymandias, and it got me thinking about statues, and our nature as humans to revere them. Humans, afterall, have always been obsessed with leaving something behind. Not just stories or names, but things: stone and steel and marble arranged in ways meant to outlast the fragile bodies that built them. Monuments are our attempt to speak across time, to say we mattered, even when no one is left to remember why.

I have to admit I find myself drawn to the concept of monuments because of that contradiction. I mean, at their best they act as anchors for our collective memory, preserving belief systems, victories, losses, and values a culture wants to protect. But at their worst, they’re tributes to ego: grand declarations of power carved into materials chosen specifically because they resist decay. The irony, of course, is that history has never stopped decay from happening anyway.

Poetry understands this instinct well. Poets return again and again to ruins, broken statues, and abandoned temples, not to celebrate them, but to interrogate them. Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ozymandias is perhaps the most famous example: a shattered monument in the desert, once meant to proclaim eternal dominance, now reduced to fragments swallowed by sand. In poetry, monuments rarely succeed. They linger as warnings, reminders that time erodes authority as surely as it erodes stone.

Magic: The Gathering, however, asks a different question. What if monuments did work?

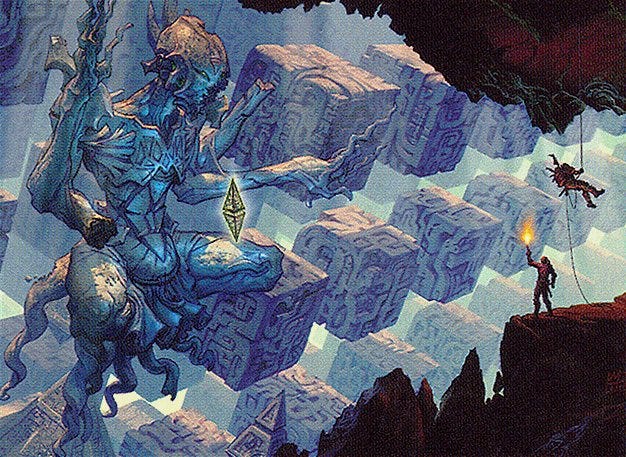

When I look at a card like Forsaken Monument, I don’t see failure or decay. I see a structure that still produces value long after its creators are gone. Mechanically, it rewards devotion and amplifies power. Visually, it evokes something ancient and abandoned. But unlike Shelley’s ruined statue, this monument hasn’t lost its purpose, it’s become more potent through use. In Magic, forgotten temples don’t fade into irrelevance. They just become engines.

That contrast is what this article is about. Examining how monuments are treated in poetry, particularly Ozymandias, alongside how they function in Magic, I want to explore two very different approaches to legacy. Poetry is skeptical of permanence; Magic indulges in the fantasy that what we build can continue to matter. Somewhere between ruin and resource, monument and mana, we find a conversation not just about art or gameplay, but about what we hope will remain after we’re gone.

A Monument by Any Other Name

Before we dive in, let’s set the parameters for what a “Monument” is. At its simplest, a monument is a structure built to be remembered. This definition sounds almost too clean, but it’s useful precisely because it leaves room for complexity. Monuments aren’t always just statues of rulers or towering obelisks, they can include temples, memorials, shrines, and even entire city layouts designed to communicate meaning across generations. A monument doesn’t just exist in space; it exists for time.

What makes the structures especially compelling to me is that they are never neutral objects. Every monument encodes intention. Someone chose what to commemorate, how large to make it, what materials to use, and where to place it. Those choices tell us what a culture valued and, just as importantly, what it wanted others to believe it valued. Monuments shape memory as much as they preserve it.

Historically, monuments tend to fall into a few overlapping categories. Some are built to assert power: statues of rulers, victory arches, towering symbols of empire meant to dwarf the individual viewer. These would be your Chris Columbus Statues, your Arc De Truimphes, etc. Others are devotional, constructed to honor gods, ideals, or cosmological beliefs like Cathedrals and Shrines. Oftentimes these others function as sites of collective mourning, asking communities to remember not triumph, but loss. Regardless of their purpose, all monuments share a common desire: to make meaning permanent.

That permanence is where monuments begin to brush up against fiction, myth, and eventually games like Magic: The Gathering.

When Magic presents us with a card like Forsaken Monument, it’s drawing from this same tradition. The card isn’t just an artifact in the mechanical sense; it’s a signal that something old, important, and powerful once stood here. Even in a fantasy setting, monuments serve the same narrative function they do in the real world: they imply history without having to explain it.

What’s the Big Deal?

Monuments matter to humans because memory is fragile. Long before written history was widespread, monumental architecture served as a way to stabilize stories that might otherwise be lost. Stone outlasts oral tradition. Scale commands attention. A monument ensures that even if the details fade, something remains to mark that moment, belief, or person once held significance.

Throughout history, these idols have been deeply entangled with power. Ancient Egyptian obelisks and pyramids weren’t just tombs; they were declarations of divine authority and cosmic order. Roman columns and forums celebrated conquest and governance, embedding political dominance directly into the urban landscape. Medieval cathedrals reached upward not just to honor God, but to make faith physically unavoidable. To encounter these monuments was to be reminded of your place within a larger system.

And yet, what fascinates me most is not the monuments at their peak, but what happens to them over time. Empires fall. Religions shift. Cities change hands. Monuments, once central, become background—or ruins. A statue meant to inspire awe becomes a curiosity. A temple becomes a tourist site. In many cases, the monument survives longer than the meaning it was built to preserve.

This slow erosion of context is exactly what poetry seizes upon. When poets write about monuments, they’re rarely interested in their original intent. Instead, they focus on what remains once authority has drained away. A broken statue in the desert tells a truer story about power than a pristine one in a capital city. Time reframes monuments whether their builders intended it or not.

Magic: The Gathering operates on a different axis, however. Its monuments are often ancient, abandoned, or forgotten, but they never lose relevance.

A player doesn’t need to know who built Forgotten Monument or why; its importance is proven every time it amplifies mana or strengthens a board state. In this way, Magic sidesteps historical erosion entirely. Meaning isn’t lost because meaning is mechanical.

That difference reveals something fundamental about how we engage with monuments today. In history and poetry, monuments remind us that permanence is an illusion. In games, they offer a space where that illusion can safely exist. They let us imagine a world where what is built to last actually does, and where the past continues to reward those who know how to use it.

Bysshe Please

When poetry turns its attention to monuments, it rarely does so with reverence. Instead, poets are drawn to what monuments become once the authority behind them has collapsed. Ruins, in particular, occupy a central place in Romantic literature, where they function not as nostalgic artifacts, but as critical tools—ways of interrogating power, legacy, and the illusion of permanence.

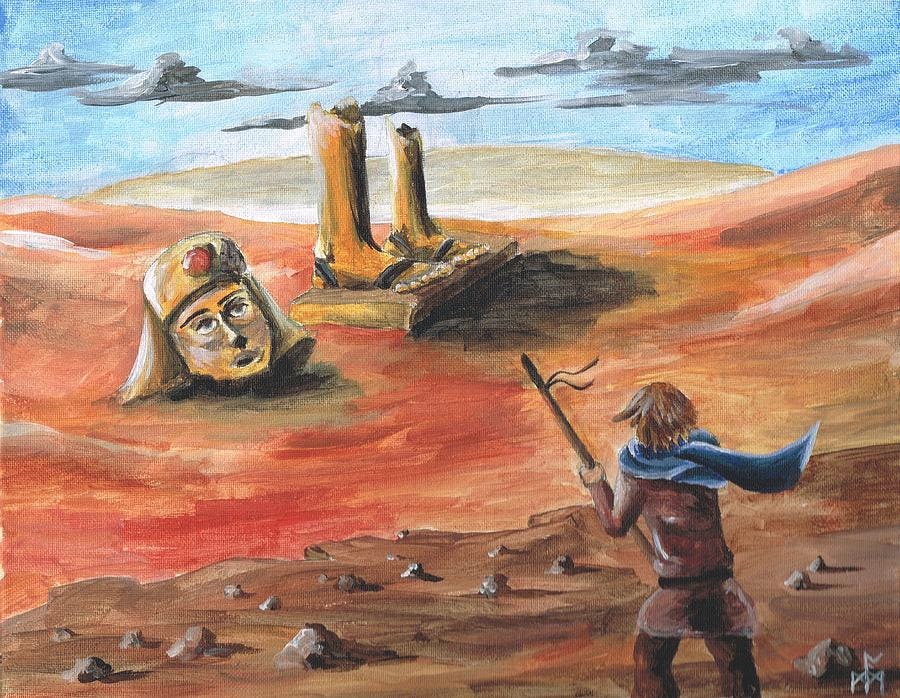

Percy Bysshe Shelley’s Ozymandias (1818) emerges directly from this tradition. Written during the height of British imperial expansion, the poem reflects a broader Romantic skepticism toward empire and absolute authority. Rather than depicting a monument in its moment of triumph, Shelley presents it through layers of distance: the speaker hears of it secondhand, from “a traveller from an antique land.” The monument is already displaced in both space and time, its power mediated through storytelling rather than presence.

What remains of the statue is incomplete:

“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert…”

This fragmentation is crucial. Romantic scholars often note that ruins allow readers to witness the collapse of meaning in real time. The monument’s physical survival does not preserve its original function; instead, it exposes the gap between intention and outcome. Even the ruler’s expression, “the sneer of cold command,” survives only as evidence of arrogance, not authority.

The poem’s most famous inscription sharpens this irony:

“My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings;

Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!”

In isolation, the command is absurd. The imperative to despair has lost its object. As Shelley immediately undercuts the declaration—“Nothing beside remains”—the monument becomes a literary device rather than a historical one. It does not testify to greatness, but to the inevitability of decline. The longer the monument endures, the more complete its failure becomes.

From a scholarly perspective, Ozymandias exemplifies what critics often describe as the Romantic ruin: a symbol that gains meaning through decay rather than preservation. The poem suggests that monuments do not defeat time; they are reshaped by it. Authority, once severed from living systems of power, cannot survive on stone alone.

This is the dominant poetic treatment of monuments. They are warnings, not victories. They remind readers that legacy is unstable, that permanence is aspirational at best, and that history ultimately reclaims every attempt to control memory.

Which might be why Magic feels so striking in contrast. Where poetry insists on erosion, Magic imagines a world where monuments retain function even after meaning has faded. The ruin does not become irrelevant, it becomes playable. And in that shift, the monument moves from critique to engine, from symbol to system. Poetry and Magic are looking at the same object and asking radically different questions. For poets like Shelley, the monument is meaningful precisely because it no longer functions. Its brokenness exposes the lie at the heart of permanence, turning stone into evidence that power cannot outlast time.

Magic: The Gathering refuses that conclusion. Its monuments do not wait for meaning to collapse before becoming relevant; they are relevant because they still operate. A forgotten structure that no longer produces value would be narratively consistent, but mechanically unsatisfying. So Magic imagines a world where legacy is not just symbolic, but also actionable. Power is not mourned in the multiverse; it is tapped.

Now this is not a contradiction so much as a philosophical fork in the road. Poetry teaches us how monuments fail. Magic shows us what it would look like if they didn’t. By placing these two treatments side by side, ruin versus engine or warning versus reward, we can see how each medium reshapes the same cultural object to serve its own goals. The monument, it turns out, tells us less about the past than it does about how we want to interact with power in the present.

Ruins Versus Engines

One of the most striking differences between how poetry and Magic: The Gathering treat monuments is not just what they do with them, but how many they allow to exist.

Poetry, obviously, has no such constraint. Ruins are everywhere. Every fallen empire, every abandoned city, every broken statue is fair game. The abundance of monuments in poetry reinforces its central argument: power proliferates, overreaches, and inevitably collapses. The landscape of ruin becomes crowded, almost anonymous. A monument does not need a name to function as a warning. Its very brokenness is enough.

Magic, by contrast, has to be selective.

Across the entire history of the game, there are only 16 named Monuments, with 5 additional unnamed ones represented on cards. That scarcity is not accidental. In a game with tens of thousands of cards, Magic could have filled its worlds with monuments endlessly. Instead, it treats them as rare, deliberate structures; objects important enough to be named, preserved, and mechanically relevant.

This limitation reframes how they function in Magic as well. These are not casual remnants of history; they are curated. A named Monument in Magic is an intentional signal to the player that this structure matters, not just narratively, but systemically. It will produce mana. It will shape strategy. It will ask to be built around. Unlike poetic ruins, which exist to be observed, Magic’s monuments exist to be used.

So let’s talk about these monuments!

First up we have the Dragonlords of Tarkir and their monuments to subjugation and control:

These monuments offer simple value, create a mana and eventually use it to summon a disciple of the monument’s visage. Each of these artifacts exist in the same capacity as Ozymandias’ titan in the desert–assert power and demonstrate pure ego.

Luckily we have a perfect mirror to hold up to these in the form of Tarkir Dragonstorm’s Clan Monuments:

Where the Lord’s structures exemplified tyranny and fear over the world around them, these symbolize the peaceful nature that the clans have fought for. By tutoring an allied land and eventually providing reinforcements. These monuments feel like the healing of a scar left long ago.

Then we shift planes to that of Amonkhet, a plane steeped in corruption and blind faith. The monuments here, one for each of the Pantheon’s gods, are conduits. They provide mana from the natural world around them and then provide blessings from their respective deities.

To me, these are the closest things to a living, breathing, entity. Almost as if the gods themselves built them and imbued them. Where the other monuments feel constructed, these feel divine in nature.

Finally we come to the unnamed monuments. These are remnants, these, like Ozymandias’ before them, feel ancient in nature. The world has passed them, time has, in many ways, forgotten them. Yet we can feel their power nonetheless.

The unnamed monuments provide buffs, mana, card draw, and more. They are highly individualized and that feels important. Because they aren’t associated with a specific entity they provide us with the same amount of information on the world around them as that dusty plaque in Shelley’s poem.

This is where the contrast sharpens. In poetry, monuments lose their meaning as they lose their context. Their names, if they survive at all, become ironic footnotes; Ozymandias is, afterall, remembered precisely because his monument failed. In Magic, naming preserves relevance. A monument that retains a name retains function. It is not a warning about the past; it is a resource in the present.

Like I said before, even the 5 unnamed monuments in Magic feel intentional. Their anonymity doesn’t diminish their power; instead, it invites projection. They function less as specific historical artifacts and more as archetypes, stand-ins for all the forgotten structures that still hum with latent energy. In this way, Magic acknowledges decay without surrendering utility.

Where poetry allows monuments to proliferate so they can fail, Magic restricts them so they can matter.

That difference matters. It tells us that Magic isn’t rejecting poetry’s skepticism, rather that it’s responding to it. By limiting the number of monuments and insisting that they remain functional, Magic constructs a world where legacy is not assumed, but earned. A monument must justify its existence every time it’s tapped, activated, or protected.

Most often, in poetry, ruins teach us humility. In Magic, they almost teach us stewardship. Both are asking the same question, “what survives?” but they offer us radically different answers. One finds meaning in collapse. The other finds it in continuity.

And somewhere between those answers is the tension that keeps me coming back to both.

What We Choose to Leave Behind

Monuments are never just about the past. They are about what we hope the future will remember, and more importantly, how we want it to remember us. Shelley’s sonnet teaches us that those hopes are fragile, that stone erodes, empires collapse, and meaning slips away no matter how carefully it’s carved. Magic, meanwhile, offers a world where monuments still hum with power, where history can be tapped, activated, and defended.

Neither vision cancels out the other. Instead, they exist in a conversation. Poetry keeps us honest while Magic keeps us hopeful.

Somewhere smack dab in the middle, between Shelley’s ruined statue and a tapped Forsaken Monument, we find a familiar human desire: to believe that effort matters, that creation leaves a mark, and that what we build might continue to mean something after we’re gone. Whether we encounter monuments as warnings in verse or as engines on the battlefield, they reflect the same truth: that we are always building toward a future we won’t fully see.

And maybe that’s the real legacy monuments offer us. Not permanence, but participation. Not certainty, but the chance to be remembered, or at least to imagine that we might be.

Leave a comment