How Lorwyn’s Faeries Uphold the Faerie Traditions of Mischief

January 7, 2026

“Lord, what fools these mortals be.”

— Puck, A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Lorwyn is on its way, or the return anyway, and with it a cavalcade of new faeries is sure to get revealed! But what makes Magic’s faeries so exciting? What allows them to feel so innocent and evil at the same time? To better understand the ways in which Wizards explores the nature of these fae, we should look back in time, to myth and legend.

Shakespeare’s faeries don’t conquer kingdoms. They don’t lay waste to cities or topple gods. Instead, they arrive unseen, twist intentions just enough to cause embarrassment or heartbreak, and vanish before anyone can properly assign blame. Their power is subtle, social, and profoundly irritating, it’s less about domination, more about disruption. If we agree that kings rule through decree and heroes through action, then faeries definitely rule through timing.

This tradition didn’t begin with Shakespeare, of course, but his play A Midsummer Night’s Dream gave it language. Gave it teeth. Faeries became the unseen hands that rearranged the narrative while laughing at how seriously everyone else took themselves. Mischief wasn’t a personality trait to them; it was a methodology.

And if you’ve ever played against Faeries in Magic: The Gathering, you already know exactly how that feels.

Entire turns passed with not but a land played, a full grip of cards, and a smile that says, “go ahead.” Because Magic’s faeries don’t beat you in a straight fight. They don’t overpower your board or overwhelm you with numbers. They show up on your end step. They tap your lands when you need them most. They counter the spell you were sure would resolve. They don’t destroy your plan so much as politely inform you that it was never going to happen.

What Magic accomplished with Lorwyn, and faeries in general, wasn’t just an aesthetic homage to English folklore, it was a translation. Shakespeare’s meddling spirits, Celtic tricksters, and pastoral faerie courts were converted into flash timing, permission spells, and tempo manipulation. The result is a deck, a tribe, that doesn’t just reference literary faeries, but behaves like them.

In this article, I want to trace that lineage: from myth, to Shakespeare, to gameplay. Not to argue that Lorwyn’s faeries are inspired by literature, (we already know that) but to show how Magic turned mischief itself into a playable experience. One where, just like in the woods outside Athens, the real danger isn’t losing the fight.

It’s realizing the game was never being played on your terms at all.

Before the Wings and Glitter

Before faeries were small, cute, or marketable, they were unsettling. In the mythological traditions of the British Isles, faeries were not creatures of comfort or wish fulfillment, they were explanations for the world slipping sideways. Lost time. Misfortune without cause. A familiar path that suddenly led somewhere it never had before.

Early Celtic and British folklore places faeries firmly in the liminal. They live at the edges of things: twilight instead of day or night, hills instead of houses, crossroads instead of straightaways. They are not spirits of good or evil, but of the in-between, liminal beings who operate in the gaps humans don’t quite know how to guard. To encounter a faerie was not a blessing or a curse, it was more of a disruption.

And disruption is the point.

Faerie mischief in myth is rarely random. It is reactive, conditional, and often instructional. A poorly worded bargain, a breach of hospitality, or a moment of arrogance invites correction. Milk spoils. Tools vanish. A traveler loses an entire night to dancing and wakes decades later. These stories aren’t about cruelty so much as consequence. Faeries punish certainty, especially the human assumption that the world will behave predictably.

Crucially, faeries do not assert power through force. They don’t conquer land or rule openly. Their influence is exerted sideways: through tricks, illusions, time distortion, and social embarrassment. A faerie wins not by being stronger, but by being earlier, quieter, or simply unexpected. Strength is visible. Mischief is not. This is why size matters so little in faerie myth. We see this in the SiFi series The Magicians when they are depicted as towering sidhe or unseen household spirits. Faeries are consistently framed as powerful because they refuse direct confrontation. They manipulate context rather than outcomes. A faerie would never stop you from walking down the path, they just make the path stop being what you thought it was.

There is also an inherent communal logic to faerie folklore. Faeries rarely act alone. They belong to courts, hosts, rings, and revels, networks of influence rather than hierarchies of command. Individual faeries might be clever, but the collective is what enforces consequence. Break the rules of the world, and the world responds, softly but thoroughly. Over time, later folklore and Victorian reinterpretations sanded down these edges. Wings were added. Danger was replaced with whimsy. Mischief became harmless play instead of narrative threat. But beneath those layers, the original function of faeries remained intact: to remind humans that control is an illusion, and that certainty is an invitation.

It is this older tradition, the faerie as liminal disruptor, rather than benevolent sprite, that survives most faithfully in English literature. And it is this version of faerie myth that Lorwyn quietly resurrects, not in flavor text alone, but in the way its faeries refuse to let the game proceed as expected.

Faeries in English Literature

On our way to the MtG portion of this piece, I just want to explore the literary background of faeries as well really quickly. Because when English literature inherited the faeries, it didn’t tame it, it just gave them a stage.

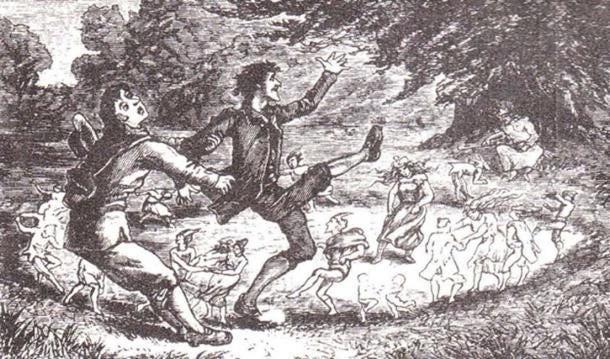

By the time Shakespeare wrote A Midsummer Night’s Dream, faeries were already culturally understood as meddlesome, unpredictable, and dangerous in subtle ways. What Shakespeare did was crystallize their function. His faeries are not monsters lurking at the edge of the world; they are active participants in human drama, gleefully reshaping it while remaining largely untouched by consequence themselves.

Puck, aka Robin Goodfellow, is the clearest expression of this literary faerie tradition. He does not act out of malice. He acts out of curiosity, boredom, and delight. His mistakes are not accidents in the moral sense, but in the logistical one. He applies the wrong spell, to the wrong person, at the wrong time, and the fallout becomes the play. Love is misdirected. Authority is undermined. Certainty collapses. And when Puck observes the chaos he’s caused, he laughs.

This is the defining shift English literature makes: faerie mischief becomes narrative control. Faeries do not merely disrupt events; they decide which events matter at all. They alter perception rather than reality, and in doing so, they reveal how fragile human intention really is. Nothing in A Midsummer Night’s Dream is destroyed by the faeries. It is simply rearranged until everyone involved is forced to confront how little control they ever had. Importantly, Shakespeare’s faeries do not challenge power head-on. Oberon does not overthrow Theseus. Titania does not wage war on Athens. Instead, they bypass human structures entirely. Kings, lovers, and craftsmen alike are reduced to playthings, not because the faeries are stronger, but because they operate on a different axis of power altogether. While humans argue over law, honor, and love, faeries rewrite the conditions under which those arguments make sense.

This is where the literary faerie most clearly diverges from later fantasy interpretations. Shakespeare’s faeries are not noble guardians of nature, nor are they cute tricksters meant to charm the audience. They are unsettling because they are correct. They expose folly by letting it run unchecked. When Puck calls mortals fools, it isn’t an insult, it’s just an observation.

English literature repeatedly returns to this version of the faerie: the being who destabilizes human systems by revealing their absurdity. Faeries don’t win battles. They don’t need to. They make the battlefield irrelevant. And crucially, they always act at the margins: offstage, between scenes, during moments when humans assume nothing important is happening. Their power is tied to timing, not spectacle. They arrive late, leave early, and change everything in between.

This literary tradition sets the perfect precedent for what Lorwyn would eventually do in Magic: The Gathering. Because when Magic finally translated faeries into gameplay, it wasn’t interested in giving them swords or armies.

It gave them the ability to interrupt.

To act at the wrong moment.

To make fools of mortals who thought the game would unfold politely, predictably, and on their turn.

Lorwyn as Pastoral Myth

Lorwyn is not a battlefield. It is not a plane bracing for apocalypse, nor a world defined by open war or cosmic catastrophe.

Instead, Lorwyn exists in a state of perpetual daylight: pastoral, orderly, and quietly self-assured. Its villages persist. Its roles endure. The world believes, almost naïvely, that tomorrow will look like today.

Lorwyn draws deeply from pastoral myth and fairy-tale logic: a land of farms, hedgerows, and communal rhythms. Kithkin organize their lives around shared memory called the thoughtweft. Giants tend flocks, those poor goats. Treefolk stand as living monuments to continuity. Conflict exists, but it is small, contained, and local. This is a plane that assumes stability as a default.

Pastoral worlds have always been fertile ground for faerie mischief because they rely on predictability. In folklore and literature, faeries don’t disrupt chaos, that would be redundant, so they disrupt comfort. They require a world that thinks it understands itself in order to reveal how fragile that understanding really is. Lorwyn’s eternal sunlight doesn’t banish faeries; it gives them contrast.

In Lorwyn, faeries are not protectors of nature or guardians of balance.

They are watchers. Interrupters. They occupy the liminal spaces above the world: rooftops, treelines, drifting mists, always present without participating. While other tribes are grounded in labor, lineage, and place, faeries remain untethered. They define themselves by timing rather than territory.

Then Shadowmoor arrives.

Where Lorwyn is sun-drenched and communal, Shadowmoor is claustrophobic, nocturnal, and isolating. The same plane turns inward, twisting its pastoral certainty into something fearful and suspicious. Memory falters. Communities fracture. The world no longer assumes goodwill, it braces for harm.

And the faeries thrive.

Shadowmoor doesn’t create new faeries so much as remove the social constraints Lorwyn quietly imposed on them. In the absence of trust and daylight, mischief sharpens into cruelty. Secrets become weapons. The playful disruption of Lorwyn becomes the predatory manipulation of Shadowmoor. Faeries shift from meddling observers to active enforcers of fear.

This transformation mirrors faerie mythology perfectly. Faeries have always been shaped by the environment. In places of comfort, they embarrass. In places of danger, they punish. Shadowmoor strips away the pastoral buffer and reveals what faerie mischief looks like when there is no longer a shared sense of safety to push against.

Crucially, Lorwyn and Shadowmoor are not opposites; they are reflections. The same faeries exist in both, altered not by ideology but by atmosphere. Daylight produces tricksters. Darkness produces tyrants. The methodology remains the same: indirect power, psychological pressure, and control through uncertainty.

By giving us both Lorwyn and Shadowmoor, Magic doesn’t just adapt faerie folklore, it demonstrates it. The plane itself becomes a mythological experiment, showing how faeries respond when pastoral myth collapses into gothic dread. Mischief is not abandoned; it is intensified.

And when these faeries enter the game, they carry both worlds with them. The cheerful interruption of Lorwyn and the oppressive denial of Shadowmoor coexist in the same mechanics: proof that faeries were never meant to be stable.

Mischief into Mechanics

Lorwyn’s greatest achievement is not that it references faerie folklore, but that it teaches players how faeries behave by forcing them to experience it. The mechanics don’t describe mischief, rather they enact it. To play Lorwyn faeries, or to play against them, is to participate in the same pattern of disruption that defines faeries in myth and literature.

Faeries do not ask for attention. They wait.

Acting Where You Weren’t Watching

Flash is the single most important mechanical expression of faerie mischief. It allows faeries to exist in the margins of the game, appearing when nothing “should” be happening. Much like their mythological counterparts, they intervene between moments, not during them. End steps become thresholds. Safe phases become vulnerable.

Flying reinforces this sense of untouchability. Faeries don’t engage on the same axis as other creatures. They pass above conflict rather than through it, exerting influence without fully committing to the battlefield. You can see them, but interacting with them is another matter entirely.

Together, flash and flying create a constant state of uncertainty. You are never quite sure when the faeries will arrive, only that they are already watching.

Mischief as Denial, Not Destruction

Faerie countermagic feels like brute-force negation, it feels like being interrupted mid-sentence. Your spell isn’t destroyed; it is refused. The game acknowledges your intention and then quietly informs you that it will not be honored.

This is deeply aligned with faerie folklore. Faeries don’t smash doors down; they lock them while you’re reaching for the handle. They thrive on conditional permission: on rules that can be invoked or withdrawn without warning. Counterspells transform the stack into a narrative space where expectation is punished.

You didn’t lose because your plan was weak. You lost because you assumed it would resolve.

Stealing Moments

Faerie mechanics rarely remove resources permanently. Instead, they just manipulate time. Tapping lands, bouncing creatures, or delaying actions with stun counters and sleep effects, all in hopes of destabilizing it. You are perpetually a turn behind, a mana short, or a step out of sync.

This is mischief at its most literary. Like Puck applying the wrong flower to the wrong eyes. The board state remains intact, but the order of events collapses. You are forced to react rather than act.

Cards like Pestermite

and Mistbind Clique

exemplify this philosophy. They don’t overwhelm the opponent; they take a single, crucial moment and deny it. Victory arrives not through dominance, but through accumulated interference.

The Faerie Court in Motion

Individually, faeries are unimposing. Small bodies. Modest stats. But faeries are not meant to stand alone. Their strength lies in coordination: an echo of faerie courts, hosts, and revels from myth.

Each faerie reinforces the others. A single interruption becomes a pattern. A single denial becomes a lock. The deck doesn’t feel like a collection of creatures; it feels like a system enforcing its own logic.

Break one rule, and the court responds.

This collective pressure mirrors the communal enforcement found in folklore, where consequence is rarely delivered by a lone faerie, but by the weight of the unseen many. The game becomes less about individual cards and more about whether you can exist within the space the faeries allow.

Lorwyn’s faeries do not win by closing the game quickly or spectacularly. They win by ensuring the game never quite belongs to you. Every mechanic (flash, countermagic, tempo, synergy) serves the same purpose: to destabilize certainty.

Mischief, Preserved

Lorwyn’s faeries endure not because they are powerful, but because they are faithful.

Faithful to myth, where faeries existed to unsettle certainty.

Faithful to English literature, where mischief became a form of narrative authorship.

And faithful to Magic itself, a game built on timing, expectation, and the fragile hope that things will resolve the way we intend.

What Lorwyn accomplishes is not a stylistic homage to faerie folklore, but a preservation of function. These faeries do not merely look like their literary ancestors; they behave like them as well. They interrupt players, they deny actions, hell they arrive when they are least welcome and leave the game unrecognizable in their wake. I think Wizards has done an excellent job with their design as well. Afterall, the mechanics do not soften their edges, if anything, they sharpen them.

By situating faeries within a pastoral world that later collapses into Shadowmoor’s darkness, Magic demonstrates something myth has always understood mischief is contextual. In the daylight, it embarrasses. In the dark, it dominates. But it never truly disappears. It simply adapts, waits, and remembers.

This is why Lorwyn’s faeries still provoke such strong reactions years later. They are not nostalgic curiosities or charming relics of an older design philosophy. They remain uncomfortable, frustrating, and deeply effective. They remind us that control in Magic—like control in stories—is often an illusion maintained only until someone knows when to intervene.

In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the faeries restore order not by enforcing rules, but by revealing how arbitrary those rules always were. Lorwyn’s faeries do the same. They do not end the game with spectacle or finality. They end it quietly, by ensuring the game was never quite yours to play.

Mischief, after all, was never meant to be resolved.

Only preserved.

Leave a comment