Monoism, The Faller, and the Legacy of Cosmic Religion

July 01, 2025

The Stars(my keyboard) Aligned(got used)

Recently, we all encountered the Monoists in Magic: The Gathering’s latest set, Edge of Eternities, and I felt intrigued. Here was a religious order that did not simply use cosmic language to elevate their worldview, I mean, they were literally born from the debris of a collapsed star.

The Monoists practice a form of cosmic certainty that transcends species, time, and physical origin. Their founding species, the Susurians, are born from the gravitational remains of the star that birthed Point Prime, beings so massive they lens light around themselves and possess an inherent command over gravitational threads. This makes their spiritual practice not merely figurative, but physical, their communion with the Edge is as tactile as it is metaphysical.

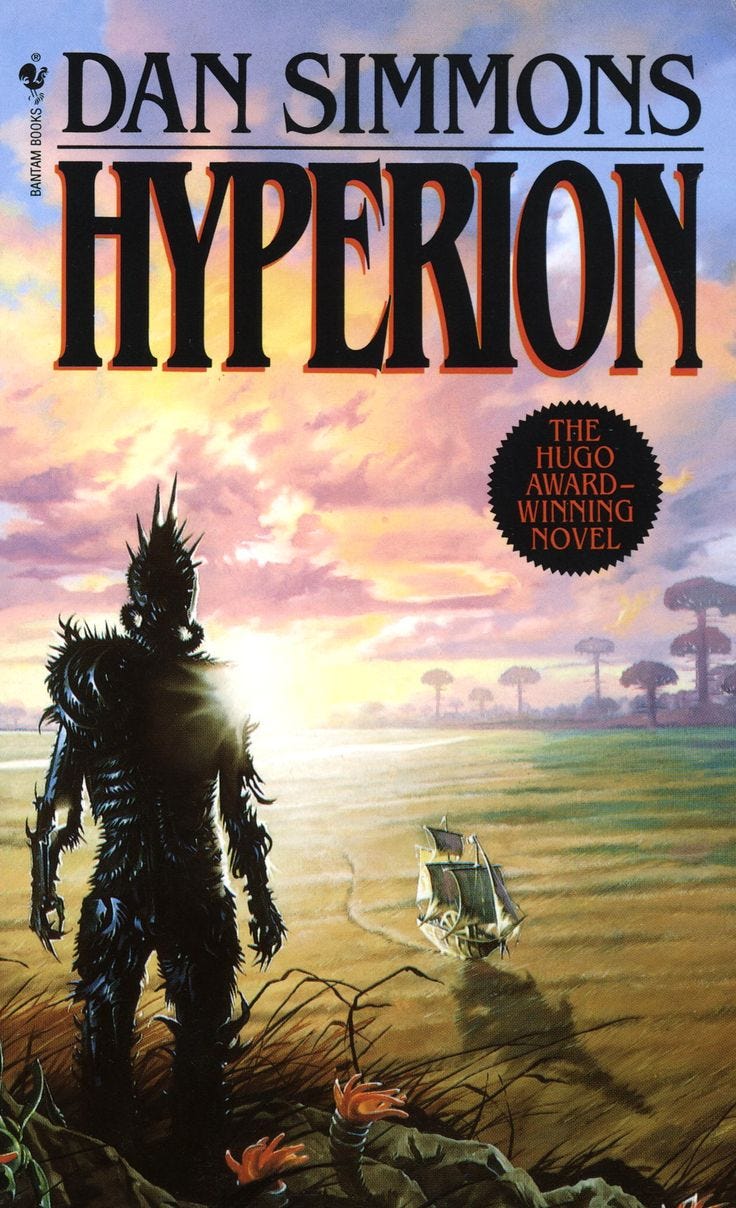

As I delved deeper into their lore, well, as deep as I can outside of reaching out to VorthosJay…which I also did…I was struck by how familiar their structure and spiritual preoccupations felt, not to anything within Magic’s existing cosmology, but to the great works of speculative fiction. The esoteric, pan-species structure of the Monoist faith recalls Frank Herbert’s Bene Gesserit from Dune (1965), a quasi-religious order of women who control political bloodlines and preserve secret knowledge across generations. Meanwhile, the Faller—a being of temporal collapse and gravitational awe descending from the Edge—evokes echoes of Dan Simmons’ Shrike in Hyperion (1989), and even M. John Harrison’s surreal and godlike Shrander in Light (2002).

These comparisons aren’t meant to diminish the originality of Edge of Eternities, but to invite a deeper reading. By understanding the Monoists and the Faller through the lens of literary science fiction, we begin to see Magic: The Gathering not only as a game or story setting, but as part of a long, thoughtful conversation about time, divinity, and annihilation. And in doing so, perhaps we find more reasons to care — not just about the cards, but about the meaning behind them. Also, if these articles are fun for you, please let me know. They are essentially scripts for video essays I wish I had the time to produce, but anyway, back to the hole lovers.

I Had Monoism Once in HS

To understand the Monoists is to understand the spiritual language of gravity. They are not simply a faction within Magic: The Gathering’s multiverse, but rather an articulation of what it means to believe in inevitability; in mass, time, and the void as sacred constants. According to the Planeswalker’s Guide, Monoism is “an ancient unitary faith commanded by an insular and esoteric governing body, the Monasteriat.” Despite its internal rigidity, the faith itself is profoundly expansive, with adherents hailing from across species and worlds, rivalling Summism for the most widespread reach in Pinnacle space.

The epicenter of Monoist doctrine is Point Prime, a supervoid — apparently it is also the largest known singularity in this region of the multiverse — encircled by the Lip of Susur, a ring of light and memory. The Lip is what remains of the star that once existed there, now stretched and thinned into a photon collar by the gravitational collapse that formed Point Prime. It is from this annular relic that the Susurians emerged. The Susurians were/are beings of massive physical density who possess an innate command over what the story terms “the trembling gravitational threads of the annular universe.”

In theological terms, the Monoists are not simply star-worshippers. They are post-stellar mystics. Their god is not the star, but the void it left behind: not the light, but the gravity. This distinction is key: for the Monoists, INEVITA is not metaphor but certainty. It is described as the next Eternity, a spiritual endpoint that exists both forward and backward in time, collapsing traditional linearity into a singular conviction.

What I find most compelling about this is the political structure of the faith. The Monasteriat, their ruling congress, is made up of “hundreds of elector monks” who guide doctrine and civil direction from the Lip of Susur. This confluence of spiritual and civic authority places the Monoists in the rare category of cosmic theocracies — where governance is not merely informed by religion, but enacted through it. It evokes not the mysticism of oracles, but the sobering deliberation of celestial judges.

Even within Magic’s long tradition of religious factions—from the Orzhov Syndicate’s corrupted afterlife economics to the Zendikari kor’s reverence for the Roil—the Monoists stand apart. Their belief is not in gods or prophets, but in gravitational inevitability. Faith, for them, is a kind of falling into certainty, into collapse, into the Edge.

Thematically, the Monoists represent a shift in how Magic: The Gathering handles religious worldbuilding. They’re not ornamental; they’re ontological. They don’t just worship something, they are shaped by it, physically and metaphysically. And that, in turn, shapes how I as a reader and player approach them. Not as zealots, but as cosmic interpreters of the inevitable.

George Michael’s “Faith”

As I read more about the Monoists, I found myself drawing an almost immediate connection to the Bene Gesserit, Frank Herbert’s iconic order of mystics, genetic stewards, and political manipulators from Dune (1965). It is possible that it’s just recency bias, I did just watch the original a few weeks ago, and, at first glance, these two institutions couldn’t be more different: one is a human sisterhood devoted to prophecy, training, and breeding; the other is a pan-species faith born from gravitational catastrophe. But the longer I sat with their respective roles, and the farther into Episode 4 and 5 I got, the more the resemblance grew, not in what they believe, but in how they function.

Both the Monoists and the Bene Gesserit operate as esoteric, hierarchical institutions that hold tremendous sway over interstellar civilizations, often from behind the scenes. Herbert’s Bene Gesserit manipulate bloodlines and guide political futures through breeding programs and deep-rooted influence, all while maintaining strict internal secrecy. Similarly, the Monoists’ elector monks guide and give “north star civic direction” for the many worlds and species under their influence. This convergence of spiritual and civic leadership doesn’t feel accidental, it feels like a hallmark of speculative religious worldbuilding, one that positions belief as not just interior, but infrastructural.

Where the Bene Gesserit rely on biological memory and ritual training, the Monoists are defined by their origin in astrophysical phenomena. Afterall, the Susurians are not just cultural leaders; they are literal products of a star’s destruction. In a way, this positions them as both spiritual avatars and cosmological inevitabilities. Their bodies, like the Reverend Mothers’ minds, carry the weight of ancient memory, only, not through lineage, but through mass.

Yet perhaps the deepest shared trait I can think of is their commitment to doctrinal certainty in the face of chaos. The Bene Gesserit cling to their designs and plans as stabilizing forces in a turbulent universe. The Monoists, meanwhile, align themselves with the The Seeker and the Faller, described as the text written by the Faller Himself, a conclusion to all things. It’s less prophecy than it is gravitational destiny. In both cases, faith becomes a tool for anchoring meaning against the entropy of time.

Of course, there are crucial differences too. The Bene Gesserit are self-directed, they see themselves as the secret sculptors of history. The Monoists, in contrast, submit to a gravitational force greater than themselves, finding peace not in control but in surrender to inevitability. The Next Eternity is not a future they create; it’s one they will join: INEVITA. This makes the Monoists far more fatalistic in tone, and more reverent in posture.

In this way, also, the Monoists do something subtle yet powerful within Magic’s lore: they invite players to engage with faith not as dogma, but as an interpretive framework. Like the Bene Gesserit, their purpose is not to convert, but to endure and live at the intersection of mystery and necessity, and to navigate the future with the quiet certainty of those who already know how the story ends.

A New God/Deity/Messiah/Falling Guy of Time(?) and Terror(?)

If the Monoists represent devotion to inevitability, then the Faller is the event that gives their certainty weight. Where they speak of the Zero Point as a metaphysical endpoint—the moment when all distinctions collapse—the Faller is the collapse made manifest. It is not simply a creature or entity in the narrative of Edge of Eternities; it is a revelation. One that terrifies as much as it confirms.

In the first episode of the official story, the Faller is described briefly. We only know that they believe that Susur Secundi was formed by the Faller. They believe this, naturally, because of the massive labyrinths and monoliths that covered the planet’s surface. They believe that you can witness Him falling at the center of every Supervoid. The hymns, or The Theorem Unending and Final as they are known, that are sung to the Faller are done so after “hearing the transmissions,” presumably made by this Singular messianic figure.

This is where Magic’s storytelling truly begins to converse with literary science fiction. The Faller shares significant thematic resonance with the Shrike from Dan Simmons’ Hyperion Cantos (1989–1997), a godlike being of pain and time distortion. The Shrike is worshipped by some, feared by most, and associated with the Time Tombs, mysterious structures that moved backwards through time. Victims of the Shrike’s attention are often impaled on its Tree of Pain, a literalization of the torment of nonlinear existence. Unlike the Faller, though, the Shrike, while it doesn’t necessarily “kill” it does reorder temporality, turning presence into suffering, worship into annihilation.

But the Faller also kind of calls to mind a stranger, more abstract figure: the Shrander, from M. John Harrison’s Light (2002). I read this in middle school so some of this is from memory if I couldn’t find the specific passage. But anyway, the Shrander appears to different characters in different forms—sometimes a robed woman, sometimes a shape made of thorns, sometimes a mocking trickster. But it is always deeply tied to the Kefahuchi Tract, a gravitational anomaly on the EDGE of a singularity; where the laws of physics and meaning begin to break down. What makes the Shrander so unnerving is not just its power, but its “impossibility.” Like the Faller, it disrupts what we know about causality and evokes a kind of cosmic dread that borders on the theological.

All three of these beings—the Faller, the Shrike, the Shrander—as dumb as that is to write out, embody what I would call an ontological threat. They don’t simply challenge characters physically; they dismantle their understanding of time, identity, and purpose. They are gods, not because they demand worship but, because they unmake the frameworks through which meaning is normally constructed.

In Edge of Eternities, the Faller represents that destined end, that collapse is not only inevitable, but sacred. Its descent within Sothera is not framed as negative in any capacity, but rather a confirmation to the Monoists. And that’s what makes it so chilling, and sick as hell. The Monoists welcome the Faller not in ignorance, but in recognition—they already understand what it means. The rest of the multiverse, it seems, is only now catching up.

What’s Good for the Shrike is Good for the Shrander

As I sit with the Faller’s brief yet haunting appearance so far in Edge of Eternities, I do find myself returning again and again to two figures from science fiction that have long lingered in my imagination: the Shrike from Dan Simmons’ Hyperion Cantos and the Shrander from M. John Harrison’s Light. These are not traditional antagonists, nor even deities in the conventional sense. They are intrusions—ruptures in the narrative order of time and self. And in that sense, they are kin to the Faller, in that they all represent an out-of-the-box view on the end, eternity, and inevitability.

The Shrike, perhaps more than any other figure in modern science fiction, embodies the terror of time dislocated. In Simmons’ Hyperion (1989), the Shrike is the godlike being associated with the Time Tombs—the aforementioned ruins that appear to move backward through time. The Shrike itself arrives unpredictably, traversing time at will, and dispatching its victims with both mechanical precision and almost mythic cruelty. It is worshipped by a cult known as the Church of the Final Atonement, who believe its violence to be redemptive and inevitable, that is the key here. The Church’s acknowledgment of the inevitability posed by the being is where the Monoistic mindset creeps in.

What makes the Shrike so compelling to me isn’t its violence, but its symbolic weight. It is the future breaking into the present. It is the consequence of choices that haven’t yet been made. And it is, above all, a form of divine silence. The Shrike never speaks. It acts. It descends. It confirms.

And this is precisely the quality I find in the Faller. When He arrives or rather, falls through the Zero Point—in Edge of Eternities, there will be no dramatic pronouncement, no exposition. Only collapse. Only the inevitable. The Faller will simply herald the journey to INEVITA. Like the Shrike, the Faller is not a villain, but a force—or perhaps more accurately, a confirmation of belief. Its presence proves the Monoists correct: the singularity is not an abstraction. It is the destination.

If the Shrike is a weaponized theology, then the Shrander is something stranger still: a trickster prophet of meaninglessness. In Harrison’s Light (2002), the Shrander appears in varying guises—to some as a robed woman, to others as a fractal being or a tormentor. It is intimately tied to the Kefahuchi Tract, the black hole that resists understanding, constantly absorbing the debris of dead civilizations and broken timelines. The Shrander does not have doctrine or hierarchy; instead, it mocks the desire for order in a universe that refuses it.

What the Shrander does share with the Faller is psychological—both in form and implication. The Faller, like the Shrander, appears to those that observe, or that’s how I’ve come to know it so far anyway. The line between future and past becomes porous. Identity flickers. Perspective bends. And while the Monoists might receive this as sacred vision, to everyone else it feels like existential collapse.

Taken together, these figures suggest a shared tradition in science fiction—one where beings of time and gravity are not mere monsters, but mythic reflectors. They return us to ourselves broken open. The Shrike rends history; the Shrander taunts comprehension; the Faller, it seems, does both. And in all three cases, the arrival of such a figure invites not explanation, but reflection. Who are we when time disobeys us? What do we believe when cause and effect fracture?

In these questions, Magic: The Gathering finds new depth. By echoing the cosmic and philosophical horror of figures like the Shrike and the Shrander, the Faller becomes more than a new villain. It becomes a theological event—and for the Monoists, a kind of gravitational Messiah.

Storytelling in the Cosmos, RIP Carl Sagan

There’s a temptation, especially in a game like Magic: The Gathering, to separate flavor from function—to read a story, appreciate its ideas, and then move on to the gameplay as if the two occupy different realms. But sets like Edge of Eternities heavily complicate that split. Here, the mechanics and the mythology are gravitationally bound. See what I did there? And nowhere is that bond more apparent than in the storytelling orbiting the Monoists and the Faller.

What fascinates me most is how the Monoists aren’t simply narrative window dressing — they are a theological lens for the entire set. In a setting where a supernova collapses and planets fracture, they provide the one thing that endures: a belief that the Supervoid, and all that it entails, is not chaos but completion. And this is not new in speculative fiction. Science fiction has long trafficked in the theological implications of collapse.

In Hyperion, Dan Simmons uses the Shrike to force his characters, and readers, to confront the terror of nonlinear time. It’s not just a plot device, but a metaphysical challenge: can you still believe in cause and effect when a god walks backward through your life? Similarly, M. John Harrison’s Light offers no comfort in the presence of the Shrander. It is a trickster of gravity and guilt, haunting its characters through what they cannot understand. Both novels demand participation—not just in plot, but in meaning.

The Monoists ask the same of us. They invite players to consider Magic’s cosmology not as a backdrop but as lived metaphysics, one where cards are not just spells and creatures, but ritual expressions of a world governed by gravitational devotion and existential collapse. That in the face of immense, cosmic inevitability, belief, and the people who hold it, become the only form of orientation.

And as players, we are not outside of this. When we build decks around temporal recursion, or engage with cards that reference voidpoints, gravity wells, or Monoist rites, we are not just selecting tools, we are participating in the symbolic language of the set. That participation is where Magic thrives. It’s what elevates the game from combat math to shared mythmaking.

This is why I believe Edge of Eternities deserves not only to be played but read. The Monoists, the Faller, Sothera itself—they aren’t just part of the narrative to me; they’re commentaries on how we handle inevitability, on what it means to believe in something vast and incomprehensible. And if we let them, they can enrich the game far beyond the battlefield.

At the Lip of Susur

The Monoists are not just a new faction in Magic’s ever-expanding multiverse; they are an invitation for us, a call to look beyond what we play and into what we believe. Through them, Edge of Eternities becomes something richer than a science fiction setting. It becomes a meditation on collapse, continuity, and cosmic belonging. It asks not only what happens at the end of all things, but what we might become on the way there.

In fiction, they stand among the great orders of sci-fi religion: the Bene Gesserit, with their generations of selective breeding and political foresight; the followers of the Shrike, who welcome pain as prophecy; the haunted spaces of the Shrander, where language, and self, fall apart. All of these stories, and of course, Magic’s own, turn their eyes toward the gravitational and the sacred, toward the uncanny intersection of physics and faith.

The Susurians, born from the lightless edge of a dead star, do not cry out. They resonate. They move slowly. They fold the language of certainty into doctrine. And when the Faller plummets, they do not resist. They recognize.

One orbit,

one ruin,

One Fall through folded light.

We become what

Waits at the

Edge.

Leave a comment